Union propaganda introduced Santa Claus to America

Thomas Nast's Civil War cartoons created the modern image of Santa Claus

By December 1862, soldiers had been fighting for nearly two years in the bloody and arduous Civil War. Neither side saw an end in sight, and decreasing morale neutralized any remnant of holiday spirit. While Union soldiers could count on little, they knew one guy had their back. No, not Abraham Lincoln – Santa Claus.

In January 1863, Harpers Weekly featured the first modern depictions of Santa, drawn by the “father of political cartoons”, Thomas Nast. Born in Germany, Nast immigrated to the United States at 6 years old in 1846. In 1862, he was hired by Harpers Weekly to create art that would move northern readers and advance support for the Union cause. Nast’s use of symbolism and powerful imagery created some of the most evocative and iconic political art of the 19th century. Throughout his long career, he depicted union camps celebrating Christmas, the plights and sorrows of the enslaved, political scandals, and corporate abuses, evolving not only the mediums that journalists could tell their stories but the trajectory of the nation.

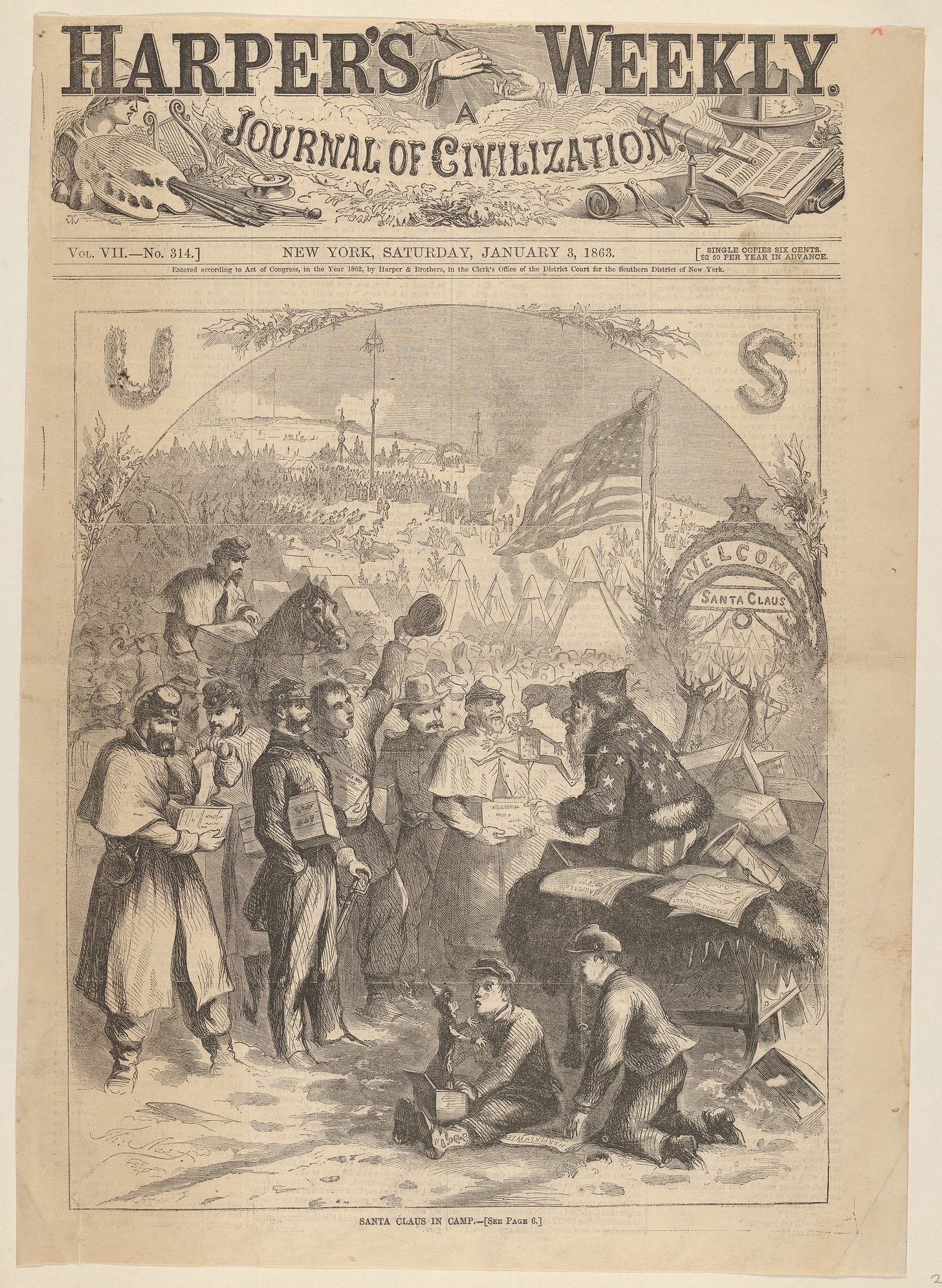

The 1862 Christmas edition of Harpers Weekly, published in January 1863, featured two of Nast’s most culturally significant works, introducing the modern conception of Santa to America. The cover image, “Santa Claus in Camp”, shows a Union camp with unending layers of soldiers cheerfully standing, inspecting their gifts from Santa’s sleigh. In the distant foreground, soldiers are playing games and standing around a fire. Santa, in the front of the image, is sitting on his sleigh hampered with gifts and editions of Harpers Weekly. He has a long white beard and is wearing a jacket adorned with stars – a compliment to his striped pants. Santa entertains a group of soldiers, showing off a puppet of Jefferson Davis being hanged. The Union flags confidently waves over an arch that reads “Welcome Santa Claus.” Just behind the sleigh, two young boys dressed in Union gear sit on the ground and play with a jack in the box – a reminder of the boyhood innocence neglected by battle.

Before 1862, children imagined Santa as a saint-like figure, dressed like a priest. Nast presents the patriotic Saint Nick as a proud supporter of the Union. With a long white beard and comforting characteristics, Americans now had a firm idea of what Santa looked like – and where he aligned politically.

Both sides celebrated the holiday in their camps. Some men placed trees at the front of their tents, others received gifts from their superiors. John Haley, of the 17th Maine, seemed to experience Nast’s drawing firsthand, writing, “It is rumored that there are sundry boxes and mysterious parcels over at Stoneman’s Station directed to us. We retire to sleep with feelings akin to those of children expecting Santa Claus.”

Within the same edition of Harpers Weekly, Nast shows a less jolly scene. Titled “Christmas Eve”, a mother solemnly prays while her children sleep in the foreground. Hanging adjacent to the decorations that surround the children’s bed is a portrait of their father, a soldier. In the opposite image, he sits, alone at a fire, reflecting on pictures of his family. The contrasting scenes show the shared loneliness weighing on the family. Frames around the family show scenes of a freshly covered grave sight, an impending battle, and a sinking ship. In the top left, Santa climbs into a chimney with his sleigh and reindeer beside him. In the top right, he’s tossing out gifts to a Union camp.

The melancholy depiction in the second drawing contrasts with the celebrations in the first. While Christmas provided Americans with a sense of normalcy, it emphasized the anguish of missing husbands, destroyed communities, and uncertain futures, both on the battlefield and the homefront. Nast’s pieces convey the complicated and often conflicting emotions felt on Christmas in a war-torn country.

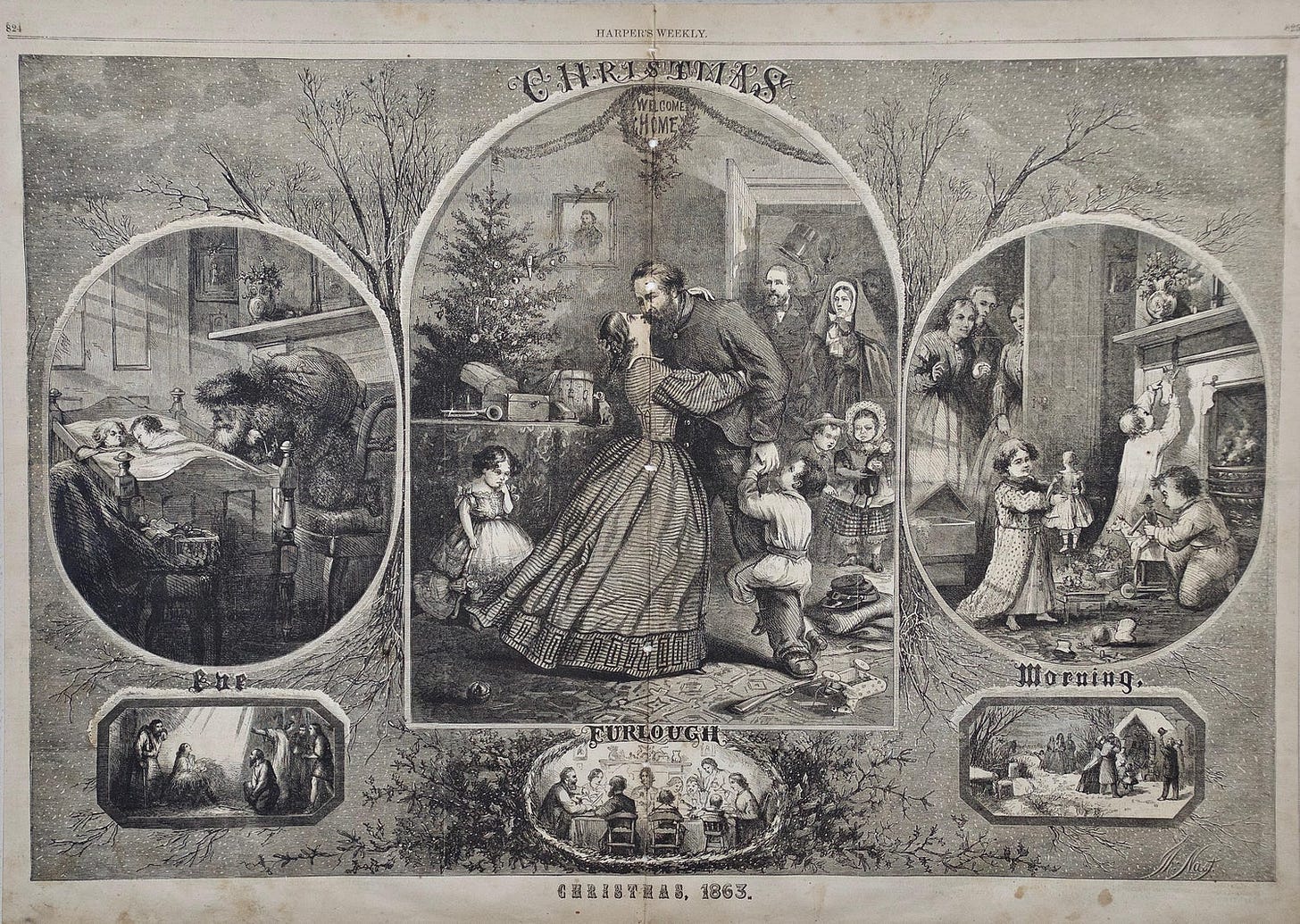

Nast’s drawing in the Christmas edition of Harpers Weekly in 1863, once again showed the service family, this time reunited – a gleam of hope as the tides of war turned towards the Union. Three images comprise the story told in “Christmas 1863”. In the first, the two children sleep soundly as Santa, with his robust white beard and stuffed sack, fills their stockings and leaves gifts. In the center, the formerly praying mother embraces her furloughed husband as their son wraps around his father's leg, gripping his hand. Gifts surround the sparsely decorated tree as guests peer in from the doorway. In the third image, the children are seen opening and playing with their gifts on Christmas morning.

In 1882, Nast refined his Santa Claus introduced 20 years earlier (this time in color), again with an underlying political intent. To the observer in 2022, “Merry Old Santa Claus” looks like a classic image of Santa – a jolly bearded man, dressed in a radiant red suit, carrying gifts of all sorts. Through subtle symbolism, Nast uses Santa to rally support for increased military wages. On the side of Santa’s bulbous-belly is a golden sword and hanging around his wrist is a US ribbon featured on military uniforms. Rather than his usual sack of toys, he carries a soldier's backpack. How could the federal government reject giving soldiers a raise when Santa supported their cause?

While Nast was driven politically, his depictions of Christmas introduced us to the imagery we associate with Santa today. His work's impact on Christmas is a reminder that politics affects more than policy. The debates of the 19th century formed the culture we cherish today. As we open Santa’s gifts this Christmas, we should reflect on the sacrifices and sorrows of those in the past while cherishing the history and traditions that have formed us into who we are.

Give the gift of Underlined!

Thank you for subscribing to Underlined! If you’re looking for an easy gift this holiday season, consider sharing my newsletter with a friend or family member. When they subscribe they’ll get all of my (mostly) interesting pieces sent directly to their inbox (mostly) every week – oh, and its free!