In 1876 and 1893, the United States hosted two world's fairs that displayed the potential for American greatness in the 20th century. In an age when Old World powers were dwindling, the American Renaissance sought to craft a cultural identity distinct from our descendants. The Renaissance hoped to heal the tender wounds of the Civil War and reinvigorate the shared history and nationalism of the United States. In addition to culture, the American Renaissance fostered the ambitious spirit of industry and innovation, pioneering the technological and economic powerhouse the country remains today. More than any other period, the American Renaissance shaped the United States into the figure it holds today.

The 1876 Centennial Exposition

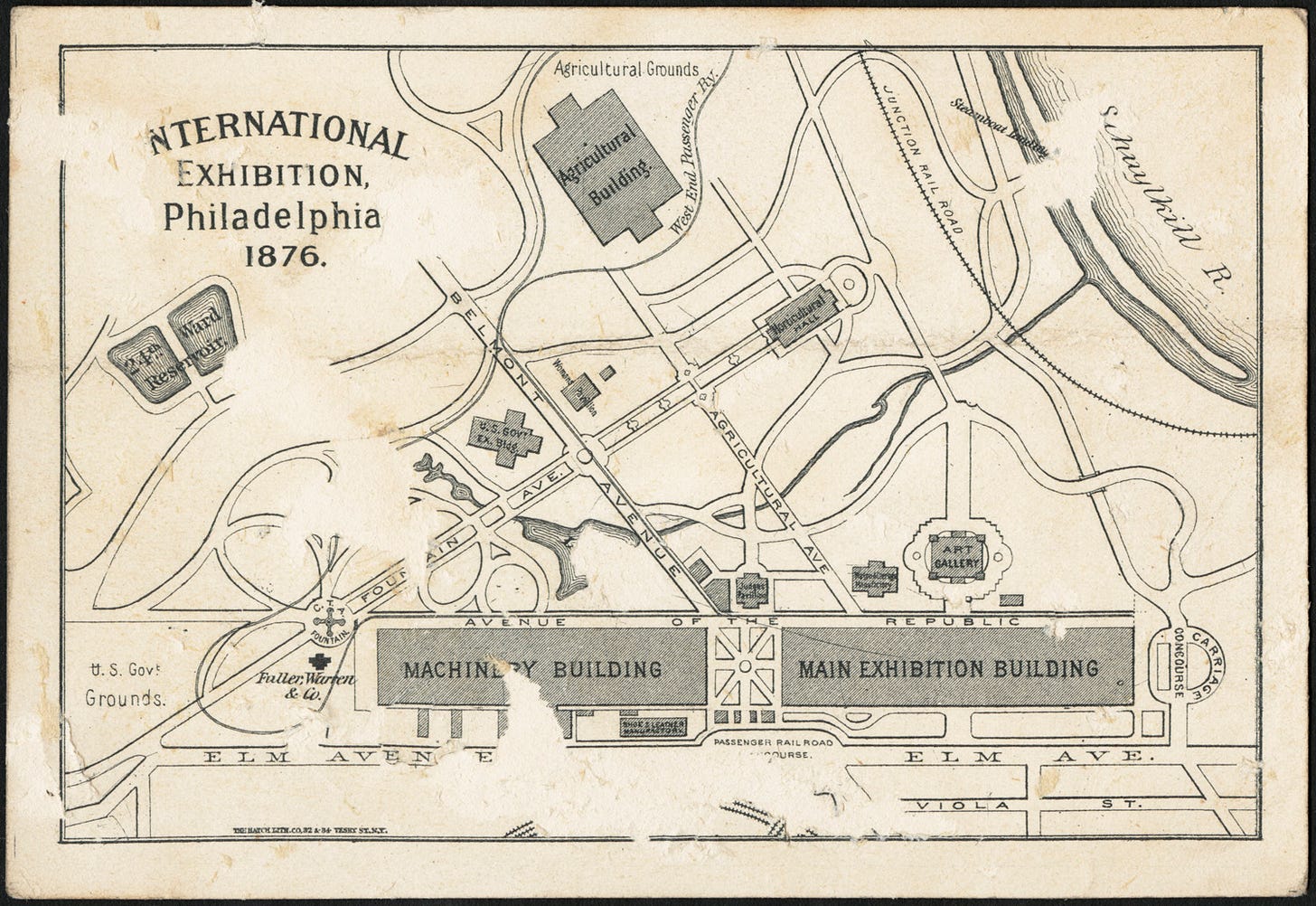

On March 3, 1871, Congress passed an act to create an exposition to celebrate the United States' centennial anniversary in 1876. The Centennial Exposition held in Philadelphia Pennsylvania began on May 10, 1876, with an opening ceremony featuring President Ulysses S. Grant. America's first world's fair ran through November displaying the greatest and most innovative inventions of the day, along with the artistic and cultural identity forming with the American Renaissance. Spanning over fifty acres, two-hundred buildings, and thousands of exhibits and showcases, the exposition had historic proportions.

Just over a decade following the end of the American Civil War, the Philadelphia World's Fair would be an opportunity for the still hotly divided nation to foster a united sense of national pride, while showcasing the United States' potential to the world. While the Centennial Commission hoped to present a united country, only twenty-six states sponsored exhibit structures, with Mississippi being the only one from the still resentful South.

In many ways, the Philadelphia Exposition symbolically marked the beginning of the Gilded Age and the American Renaissance. Exhibits were representative of the contrasting themes that would emerge during the period. After facing exclusive attitudes fostered by the planned exhibits, women raised funds to sponsor a pavilion featuring the arts, inventions, and industrial strides of women through American history.1 While the Women's Pavilion featured over 74 women-patented inventions, its organizers faced significant criticism from suffrage organizations. Activists criticized the pavilion for excluding any mention of the women’s rights movement, while upholding their second-class in society. Although their message may have been watered down by the all-male planning committee, the women's pavilion was one of the most popular at the exposition.

Black Americans had a very small role in the presentation of America and were hired for only a few menial jobs. Occurring the same year that Reconstruction would end, ushering in decades of violence and oppression, the Centennial Exposition further exemplified the discriminatory and exclusive views of the Gilded Age. Famed orator and former abolitionist Frederick Douglass was invited to sit with President Grant during the commencement, but event staff refused to allow him into the fair until white administrators stepped in. Black communities were pushed to the edges of the fair just as they were marginalized in society.

While the exclusive attitudes of the day were on full display, so were the period's industrial achievements. Exhibits displayed the greatest inventions of the day like the typewriter, improved and mass-produced sewing machines, stoves, and agricultural equipment. Machinery Hall featured an extremely powerful 36-rpm steam engine that was minimized noise and vibration. Improvements to locomotives like enhanced refrigeration cars and more powerful engines inspired the potential for the newly interconnected continent.2

The over 200 structures housing exhibits and displays were designed with grandiose imaginations of what the coming decades could bring. The Main Exposition Building was the fair's hub. Built in just over 18 months, with an iron frame and wooden features, the hall enclosed 21.5 acres, becoming the largest building in the world.3 Its exhibits from around the world focused primarily on education, science, and industry. Designed in the renaissance style, with large towers and ornate accents, the hall was reminiscent of a European castle.

Across from the Main Exposition Building, was Memorial Hall. Designed in the neoclassical style, the hall housed the exposition's great art. Built with iron framing, brick, granite, and glass, it was one of the most iconic of the fair. Featuring a large central dome accented with classical statues, the building became a model for countless museums and libraries across the nation and the world.4 The Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, and the Philadelphia Free Library modeled their iconic buildings’ organization and style on Memorial Hall.

Exhibits at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition flexed the power and potential destiny of the United States. The grand cannons and weapons shown in Machinery Hall emphasized America’s potential as a global superpower. Like the American Revolution a century early, the Philadelphia Exposition kicked off one of the most formative periods of American culture and history. Commencing the American Renaissance and displaying the nation's spirit of innovation, the first world's fair in the United States raised the expectations for success in the coming years.

The Columbian Exposition

Twenty-two years after the Centennial Exposition, the United States, now in the thick of the Gilded Age and American Renaissance, had the opportunity to host its second world's fair. In 1890, Chicago won the bid to host the exposition commemorating the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival to the New World. Organizers hoped a quad-centennial celebration of the New World's supposed founding would help further the mission of the American Renaissance and foster a shared sense of national history and culture.

Just 20 years after the Great Chicago Fire had burned most of the city, the nation's midwestern hub had an opportunity to show its unprecedented growth to the world. From 1860 to 1910, the number of cities with more than 100,000 residents boomed from 8 to 50. This rapid growth caused urban areas to lack organization and structure in their design. Industry was on top of houses, streets were tangled and discombobulated, and very little space was dedicated to parks and recreations. Columbian Exposition organizer and architect Daniel Hudson Burnham designed the layout of the fair with principles central to the burgeoning City Beautiful Movement. Burnham believed that American cities should be designed with purpose, function, and humanity while preserving their industrial capabilities. Streets should be designed to optimize movement, and zones should be drawn to maximize industry and life.

The fair's buildings were designed in the neoclassical style and assembled with cement and plaster, shaped to look like stone. Buildings were covered in a stunning white leaded-paint that earned the fair the title of the White City. The fair’s streets were lined with the bright gleaming electric lights, newly innovated by Thomas Edison. Attendees could visit attractions in the light of day, and now also in the light of night. Not far from the fences stood the cramped and inhumane tenements that were found in every major city across the country, contrasting the great prospects for the future with the dull realities of the present.

The more than 20 million people who swept through the White City, were left with the question of why every American city couldn’t be so stunning.5 Following the exposition, the City Beautiful Movement took off with journalists, progressives, and architects. Planners used the benefits and failures of the fair's layout to model their own cities’ design. The American Park and Outdoor Art Association and the National League of Improvement Associations advocated for civic memorials, parks, and permanent public attractions to cultivate urban culture and further establish a uniquely American image.6 Reformers viewed the tenements that filled urban slums as lacking the humanity the new America deserved. Architects took inspiration from the grandiose architecture of European cities to incorporate prestige into urban designs.

Since the Philadelphia World's Fair two decades prior, the United States had become a leader in the rapid innovation of industry and technology. The shining lights of the exposition were powered by Nikola Tesla’s newly invented electric induction generators. While the transportation pavilion featured mostly innovations in shipping and rail transport, two “horseless carriages” were on display – one gas-powered and the other electric. One of the largest exhibits was the world's first ferris wheel. The attraction was one of the most popular, and in the years following was replicated in cities around the world. Visitors were exposed to the culture and food that are synonymous with the United States today like hamburgers, hotdogs, and Coca Cola.

Organizers displayed very few achievements made by Black Americans since the abolishment of slavery thirty years earlier. In response to the exclusion of Black voices and exhibits, activists Ida B. Wells, Frederick Douglass, Irvine Garland Penn, and Ferdinand Lee Barnett wrote The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World's Columbian Exposition. The pamphlet was written to educate domestic and international visitors of the achievements their race had pioneered since 1865, while highlighting the violence and dangers that faced them throughout the South.7 Showcases featured racist imagery and derogatory cartoons of not only Black Americans but of other non-European nationalities. Native Americans, Africans, and Asian representatives were derided as uncivilized and barbaric. While the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition had virtually no exhibits featuring Black Americans, the somewhat evolved attitudes of 1893 allowed for some inclusion. Black women were given a small exhibit in the back corner of the Women’s Building and a handful of events featured Black speakers and panelists. While the exclusion of Black voices was less severe than in 1876, the white organizers of 1893 were only so progressive.

Women also faced discriminatory attitudes and depictions in Chicago. The exposition’s Women's Building was much larger and more prominent than Philadelphia’s in 1876. While the hall was bigger, it was still criticized as treating women as second-class citizens. The building featured art, inventions, and literature exclusively made by women. Critics argued that a building reserved only for women's achievements excluded them from seeming worthy of being featured in the main pavilions that had almost exclusively male works.

The Columbian Exposition was one of the most influential and formative events of the American Renaissance. From influencing how our cities are built, to introducing new styles and technology to the public, the 1893 world's fair can be viewed as the peak of the American Renaissance, forming the culture we associate with the United States today.

The Art of the American Renaissance

One of the main objectives of the American Renaissance was to create an American cultural identity. Like the many European renaissances throughout history, art was a driving force of culture in the rapidly growing nation. The architects, painters, sculptures, and writers of the period created the great works that are synonymous with America today.

Paintings like “Puritans Going to Church” (1867) by George H Broughton and “American Progress” (1872) by John Gast used art to promote nationalism. Broughton's “Puritans Going to Church” harkened viewers back to the early days of America’s roots, fostering a sense of shared community and history. Gast’s “American Progress” moved viewers by displaying the United States' westward destiny, guided by angels. Works like these and others display the nationalism fostered by the American Renaissance, inspiring the Gilded generation to harness American greatness.

Sculptors like Daniel Chester French used similar symbols and passions to drive their art. In commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Revolutionary Battle of Lexington and Concord, French sculpted “The Minute Man” in 1875. The 7-foot bronze statue was cast from melted Civil War cannons, while reminding Americans of the shared patriotism of the North and South during the Revolutionary era, seeking to reignite a sense of national identity.8

While the American Renaissance hoped to unite the nation, Northern and Southern artists embraced the period's style in unique ways. Sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens was selected to create a statue to commemorate Union Civil War hero William Tecumseh Sherman. Saint-Gaudens strenuously crafted every detail of his grand vision until its completion in 1902.9 The gilded-bronze statue depicts the stoic Sherman atop a horse, led by an angel. Saint-Gaudens also sculpted Boston Common’s widely acclaimed “Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Regiment” in 1897. The 34x44, bronze sculpture commemorates one of the first Black union regiments during the Civil War. While the North commemorated their Civil War victory, the South idolized their treasonous leaders. Sculptor Jean A Mercie was commissioned to sculpt Confederate General Robert E Lee for Richmond Virginia. The 60 ft bronze statue was the largest in the South, and stood as a symbol of the South's attempt to preserve slavery and the Lost Cause until 2022. While the renaissance hoped to sew unity, regional divides persisted.

The lessons of the American Renaissance and the Gilded Age reflect profoundly on the United States today. As we move further into the 21st century we must continue to examine and redefine our national identity. To inhibit our prospective characteristic, we must embrace the spirit of the American Renaissance while rebuffing its discriminatory and exploitative tendencies.

Puckett, John L. “West Philadelphia Collaborative History - Gender and Race at the Centennial Exposition.” West Philadelphia Collaborative History, https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/stories/gender-and-race-centennial-exposition. Accessed 2 March 2023.

Singh, Manpreet, et al. “Machinery Hall, Centennial Exposition 1876, Philadelphia | World's Fair Treasury.” Digital Collections, https://digital.lib.umd.edu/worldsfairs/result/id/umd:984. Accessed 2 March 2023.

Schwarzmann, Hermann J. “1876 – Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia.” Archiseek, https://www.archiseek.com/2010/1876-centennial-exposition-philadelphia/. Accessed 2 March 2023.

Tai, Tim, and Joseph A. Gambardello. “What happened to the buildings from the 1876 Centennial in Fairmount Park?” Philadelphia Inquirer, 7 May 2019, https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia/centennial-exposition-1876-buildings-fairmount-park-20190507.html. Accessed 2 March 2023.

Cashman, Sean Dennis. America in the Gilded Age: from the death of Lincoln to the rise of Theodore Roosevelt. New York University Press, 1984.

Hines, Thomas S. “Architecture: The City Beautiful Movement.” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/61.html. Accessed 2 March 2023.

WTTW. “Early Chicago: The 1893 World's Fair.” WTTW, PBS, https://interactive.wttw.com/dusable-to-obama/1893-worlds-fair. Accessed 2 March 2023.

Cheek, Richard. “The Minute Man statue by Daniel Chester French - Minute Man National Historical Park (U.S.” National Park Service, 8 July 2022, https://www.nps.gov/mima/learn/historyculture/the-minute-man-statue-by-daniel-chester-french.htm. Accessed 2 March 2023.

NYC Parks. “Grand Army Plaza Monuments - William Tecumseh Sherman.” NYC Parks, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/grand-army-plaza-m062/monuments/1442. Accessed 2 March 2023.

Great article. have been researching various fairs as background for a stamp collection of US stamps celebrating Fairs and Expos. Have also used http://www.studylove.org/worldsfairs.html